OWEN LEO GILL (LT.)

I'm not going to precis this page. Instead I'm going to let the protagonist tell his own story in a copy of a letter he wrote while he was convalescing in Egypt. Some of his descriptions relate to comparisons with Dromineer and Lough Derg and are all the more personal for that. The letter was addressed to his father John Gill detailing his harrowing experiences at the disastrous landings at Suvla Bay, The letter was later published in The Freeman Journal , 20/10/1915. It's surprisingly frank and has escaped the blue Army censors pencil.......

BundesArchiv photo of Suvla Bay 1915 from Battleship Hill

THE SUVLA BAY LANDING.

“VIVID STORY BY LIEUT. GILL.

“DESPERATE FIGHTING DESCRIBED.

“WOUNDED BURNED TO DEATH.

“COMRADES ON THE BATTLEFIELD.

“The following interesting extracts, giving a description of the Suvla Bay landing and the subsequent heavy fighting, are from a letter from Lieutenant Owen Gill, R.E., to his father, Mr. R. J. Gill, C.E., of Fattheen, Nenagh. Lieut. Gill is a relative of Mr. [?] P. Gill, secretary of the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction.

“Lieutenant Gill, who is the signal officer to the 32nd Brigade, 11th Division, is now in hospital at Cairo, suffering from shell concussion.

“After some weeks of war and changes and “alarums” and excursions, it is time that I sat down and gave you a history of my doings. I have made various notes and scribblings during August and September, and I now collect them in the form of a letter. I had some sketches made, but lost most of them, along with the greater part of my kit. You will have read all about the new landing and Suvla Bay long ago, but I warn you to believe only hald of the newspaper accounts. I must say that all newspaper news from the front here is greatly inaccurate. The only thing you can believe will be Sir Ian Hamilton's despatch, which ought to be out very soon. Towards the end of August [sic] we were occupying trenches at Cape Helles, in front of Krithia and Achi Baba, simply holding the line, and our only casualties were from stray shells and snipers. I told you about the heat and the stench and flies in a previous letter. My job was very easy there – simply keeping an eye on the lines and on the battalion signallers. Telephones were working well, and we were getting acclimatized.

“About the first of August the Division was withdrawn from Cape Helles (south point of the Peninsula), and we were shipped, horse and foot, and artillery to ______ to refit and reorganise. While we were there we spent the time practising landings from lighters, dashing ashore, forming up and doing practice attacks. Of course, we all guessed what this meant. Meanwhile the 10th (Irish) Division, (our “sister,” as we call it) was doing the same stunt on another spot. Well, to cut a long story short, on the night of the 6th of August the 32nd Brigade was shipped in destroyers, tugs, lighters, and trawlers to Suvla Bay, north of Anzac and Gaba Tepe (look at map) and we were followed by the 33rd and 34th Brigades. As we passed along the crest of the Peninsula, in the dark, moonless night we could see a battle lighting up Anzac and Gaba Tepe – the Australians making a demonstration to keep the Turks' attention occupied for our swoop. At 10 p.m. the flotilla formed up in a line. We could see nothing but a blur of distant hills and the faint dull white of a long strand.

“PREPARING TO LAND.

“A muttered order from the Commander of each transport: 'Prepare to land' (each of us transmitted the order to our sections); 'bayonets will be used till dawn'; 'no retreat to be sounded'; 'objective of Brigade to capture the high ridge and Bijuk Anafarta'; 'iron rations and water to last four days'; 'dig in when ridge is taken'; 'telegraph lines to be laid from beach to advanced positions.' Then follow detailed orders as to prisoners, rules of warfare, and a few words of encouragement. The first lighters are beached on the shore, and in a few minutes the whole Brigade is formed up on the beach. The 33rd Brigade is to land lower down, and the 34th is in support. The 10th Division is to land the next morning in front of the Salt Lake. Now, how can I give you any impression of our feelings at having effected a hostile landing in the enemy's country? Imagine yourself breaking into a house, every member of which is likely to shoot you if you make a noise. The tension did not last long. The 6th York Regiment were already bayoneting on Lala-Baba, the 9th West Yorks hot on their heels. Then a rattle of musketry breaks the night, and the atmosphere is so still that I and my section following the advance can hear the cursing and stabbing and thrusting, laughter and cheers and warwhoops. We are getting our line spun out fairly fast, and soon we have got communication between the landing beach and the top of Lala Baba. It is now about 12 p.m., [sic] suddenly a star shell lights up one of our battalions advancing. This is the fore-runner of a hail of Turkish fire. You must remember that all this time we were not firing a shot.

“TURKS FLEE.

“The Turks have been surprised in their look-out trenches, all along the coast, and they are fleeing into the interior firing as they go, and raising the alarm all over the Peninsula. Unless we get that ridge before dawn they will have guns in position and will have brought up reinforcements. The bullets are now spattering the ground, and men are dropping all over the place. A man (Lieut. Hopewell) beside me now in hospital was hit through the lungs as he was asking me had I seen any stragglers from his battalion, On the ground as I looked at him he was hit twice again. Then the cry of “stretcher bearers” begins; young fellows howling when they are hit and old fellows cursing, and some praying. Meanwhile the support battalions push on, and we know the other two battalions have landed. Imagine the scene in the darkness. None of us had the faintest feeling of fear, only we were all hoping for the dawn to get our lines secure and see the wounded and reorganise the battalions.

“As dawn breaks I find myself with a telephone station going hard on the top of Lala Baba overlooking the narrow strip of land that divides the Salt Lake from the sea. This is beginning to be a regular death trap. The Turks have opened a shrapnel fire on it, and our fellows are pouring across it in hundreds and hundreds; then up the ridge on the other side, pushing the Turks back as they go.

“At 6 a.m. General Haggard [1] forms Brigade Headquarters under a bush near our telephone. He was slightly hit there, and a spent bullet went through my helmet. Their shrapnel began to burst over our heads, and two or three of my fellows go down. At 7 I get more line from the beach which has been brought up by a party which I had detailed to follow me. By this time the sun is up in all its glory. We can see the whole show now – the 10th Division landing in lighters under shell fire at the north point of the bay, the 34th Brigade on the right, south of the Salt Lake, fighting for Chocolate Hill. The 32nd Brigade, in the centre, fighting for Kudruk and the 10 Division landing and fighting for the high ground on our left facing inland. At 10 a.m. General Haggard orders me to take the telephone station across the strip [pictured] to the direction of Hill 10 as Lala Baba is too hot for us and rifle fire was preferable to shrapnel.

“LANDING OF THE TENTH DIVISION.

“All day the 10th Division was landing as well as transports or the 11th and 16th Divisions, artillery, engineers, A.S.C., supplies, horses, ammunition. There were more ships in Suvla Bay that day than would be in the harbour of Dublin in a month. Looking out to sea the hospital ships begin to arrive, and already bleeding streams of wounded are being brought to the beach where they are taking them off as fast as they can. But the ground is simply littered with dead, Turkish and English; dying and wounded men under the blazing sun calling for water. I lost three or four men getting from Lala Baba to Hill 10 and there we dug in under a sand dune. I had some marvellous escapes, but was too busy with the telephones and getting messages through and strengthening the lines, to worry about the wire.

“It was just at Hill 10 that I saw Dr. O'Carroll's son, Frank. He was advancing towards the firing line, and I shook hands with him and wished him luck. He is down in the papers as wounded, but his Company Sergeant Major (who is in this hospital tells me that young O'Carroll was killed the same day. The day wore on and.... General Haggard's leg was shattered by shrapnel, and he was carried away, and then our brigade machine gun officer (Capt Mott, [2] of whom I used to speak, was almost cut in two by a shell splinter, but he died peacefully, and actually made his will as he lay there. So our brigade staff was reduced to three the first day. We were all lonely after Mott and the Brigadier. It is no use my describing the three subsequent days. We pushed a few miles in, made a line, brigade joined brigade, and everyone dug in. Meanwhile the 52nd, 53rd and 54th Divisions landed and reinforced as also the 29th Division and a brigade of Indians. Very soon depots and bases and hospitals were set up. We actually fought for six days without sleep, and lived on biscuits and cold bully. After four days things quietened down a bit. By this time our brigade and division, as well as the 10th Division, were reduced by 50 per cent. Nearly all the battalion officers were lost.

“A GENERAL OFFENSIVE.

“On the 21st Aug. we had a general offensive all along the line, the Australians on our right, the 10th and 29th Divisions on our left. The newspaper description of the battle of 21st August is fairly accurate; hundreds of wounded were burned to death in the bush fire, and the slaughter was terrible on both sides. The Turks were literally hurled sky high by the Navy, yet they came on and held on like devils. Regiment after regiment of British was swallowed up in the vortex. My section has suffered badly. I have had several of my men killed and nearly 26 wounded and missing. My fine Sergeant Nicholls (and English public schoolman) was killed beside me with a shrapnel on the 12th August. [3] Then I lost the others in ones and twos on the 21st. My lines were cut to bits with shrapnel, and I had to keep sending out men one by one to repair them.

“I had to keep my eye on a positive network of lines, and we had to work short-handed, and short of stores and [illegible]. We had not changed our clothes or washed or shaved since 6th August. I saw lots of Clongowes men and Dublin University men alive, and dead, and wounded; too numerous to mention them here. I think the 5th Connaughts were at Anzac (E. Kelly's battalion). Roy's battalion, 5th 18th Royal Irish, were in reserve. I did not see Roy though. I met Judge Moore's son (6th Dublins); he was wounded afterwards and is here with me.

“The battle of the 21st August was the worst thing we had been through so far. My telephone communications were continually breaking down with shrapnel, besides being burnt with bush fires.

“250,000 TROOPS ENGAGED.

“There must have been over 250,000 troops engaged that day; it was glorious, and I would not have missed it for a pension. The Irish fought like hell, and we helped them to win and hold Chocolate Hill. The battle line is too complicated for me to go into details about it now. I have sufficient sketches and notes to be able to tell you all one day (D.V.) On Sunday, the 22nd, the fighting had died down somewhat, and on Monday 23rd we were relieved – a tedious proceeding – by the 30th. Then I was on the beach in some sort of safety for two or three days. On the 27th I was standing near some reserve trenches we were digging and they began to hell the place badly. On the previous days we were troubled with Taubes which dropped a lot of bombs and caused a lot of casualties among the resting troops. Well, on the 27th I was feeling pretty rotten with a touch of dysentery when a high explosive shell dropped within 30 feet of our party. I was completely knocked out; no bones broken, and not a scratch, but deafened and blinded, and generally as if Jack Johnson had hit me in the solar plexus. We had 5 killed with this shell and about 10 shell shocks.

“I was all right and able to creep about in a few hours, but I got bad again, and I was sent to the field ambulance who shipped me on board the hospital ship, and I was ordered a month or six weeks leave in Cairo. I began to get into great form, and when the Nevasa got into Lemnos all her 500 wounded and sick were transferred to the hospital ship, and about the 29th we started on our 700 miles sea trip to Alexandria. I had a bed on the deck, and the weather was glorious, with the lovely Levantine breeze, treading our way once more down the Grecian Archipelago, leaving Gallipoli behind us with its dust and blood and death stenches – for a while at least.

“There are only 15 officers left of the 150 who came out with me and I can't find any of the men on the Hospital Ships. Ashore are hospital depots at Imbros, Lemnos, Port Said, Cairo, Alexandria, Damietta, Cyprus and Malta, and lots of the people who have amputations go straight on to England. You must realise that this hospital is 800 miles from Gallipoli, and that Gallipoli is as far from Nenagh as New York, and twice as far by time.

“ABOARD THE HOSPITAL SHIP.

“The deck of the hospital ship is alive with the Lascar crew, tiny black fellows with womanish hands, white clothes and bare feet; it takes a dozen of them to give me a cup of tea, and they are always fighting with each other. The captain of the ship is very sweet to us, and tells us all about the islands. You are never out of sight of an island from Cape Helles to Crete; no sooner has one gone behind the horizon than another hoves into view, and the captain knows every one of them – population, number of acres in each and all about them. You see they are not green islands like those one sees in Lough Derg; they are any colour in the rainbow but green, with white squat houses nestling under shelter of olive clad hills and past brown and yellow volcanic-looking rocks. We have to zig zag between the islands for fear of submarines, and I may tell you hat there are infinitely more islands in the Aegean Sea than the ones you see in an average atlas; some as big as Tipperary, and others as small as Goose Island in Dromineer.

We passed by Lemnos, Agio, Strati, Andos (off Athens), and Hermopolis and Paros, Lanos, Milos, Nios, leaving Siphanti on our left, and Santorini on our right, besides hundreds of islands of which I have forgotten the names; then the south coast of Crete with great volcanic mountains. We kept within five miles of the shore all the time. This is the world of old Ulysses, and no wonder the ancients used to weave romance and epics about it all. Imagine a sea as blue as “Reckett's” blue, the islands yellow and brown, with patches of purple and red; a white fringe of seething surf, and the island dotted with its little houses, and the island dotted with its little houses, and the ever present temple on the top of every high peak.

“Turkish and Greek houses are more or less the same, cubical, with flat red roofs, and it is very hard to know a Mosque from a Greek Church, but the priests' houses are always the finest on every island at least in Imbros and Lemnos. I have had some pleasant times in Imbros and Lemnos, and from Imbros one can see the whole artillery battle in the peninsula.

“SUVLA BAY.

“Suvla Bay is a fairly fertile part of the peninsula, well wooded with cyprus and olive groves, here and there orchards of figs and all sorts of fruit and vegetables, grapes and tomatoes. Our guns have played havoc with the nice villages and houses, and all we could see were smouldering ruins when we got up.

“On the hospital ship I have curious nightmares; think the Germans have captured Fattheen and Nenagh, and that they are shelling the places, one's head gets full of fancies, and the reaction is great after the strain of the landing and subsequent fighting. Of course we are seeing [illegible] with a vengeance, and we are never prepared to see the sun set when we wake in the morning, and when one goes to sleep one never expects to see the sun rise again. We live from hand to mouth and from hour to hour. The Australians are glorious fellows [as are the] New Zealanders. I am glad to say I took part in the new landing. The Suvla Bay landing is the thing out here now, and it is the principal part of the show out here. All other landings have been tennis parties and picnics to this one. I have lost my revolver and other things, and my kit is spread about the island, God knows where.

“AT ALEXANDRIA.

“Well, we eventually got to Alexandria, and I was feeling pretty bad and did not take much interest in Alexandria, except that I saw from [my] stretcher going from the boat to the train. It was beastly hot, and all I remember is that it is a blaze of colour and a pandemonium of noise.

“Soon we were on our way to Cairo, along the flat banks of the Nile. Everything is exactly as I imagined it from pictures and descriptions. I spent about three weeks in bed here, not able to write or even think. I am almost fit again, and I was surprised two or three days ago when Joe Reynolds' brother called on me. I can't imagine how you learned I was in Cairo, as I didn't intend to worry you by telling you; but I imagine it was Nurse Kelly from Portumna (Dr. O'Kelly's sister), who wrote to some one, and it got about that way. There are quite a lot of us suffering from shell shock. It is very common here, and only caused by high explosives.

“I am up today, and they will let me out in a few days to see the sights of Cairo – Pyramids I can see them from my windows – the hospital is in a suburb, Giza, so called after the great pyramid of Giza. Heliopolis, the Zoo, and the Nile, the citadels, and mosques and minarets. I cannot give you an idea of the wealth of colour, the glorious climate, the wonderful dresses of the people. There are about 30 officers and 600 men in this hospital, all from Suvla Bay.

“I am feeling pretty groggy, but otherwise fit, and I expect to be back to Suvla for the final show soon. Judge Moore's son is in the next bed to me. We will have a good look round Cairo before we get back, as Reynolds is going to be our guide, and he knows Cairo inside out. Cairo is the Paris of the Near East, and we have dozens of visitors and people to the hospital to take us for drives and be nice to us generally.

“I am lonely without you all, but when this show is over I will be back to you all one day soon. Love to each one of you all. Forgive me for being sentimental and all that, but soldiering does make one that way. I will write in a few days to tell you of my impressions of Cairo and send something from the native bazaars.

“P.S. – Luck to the crops. Don't worry about me here. I will be Turk stalking again in a month.”

Suvla Bay - The Sphere 15/01/1915

Lieutenant Owen Leo Gill

Gill Household 1901

Royal Engineers Cap Badge

Artillery landing at Suvla Bay

Coming Ashore

25/04/1915 - Troops landing at Suvla Bay

Waiting to move forward

Waiting......!

Sir Frederick Stopford who failed to move forward

Drawing Turkish sniper fire

Checking Turkish positions with periscopes

Firing using a periscope as Viewfinder

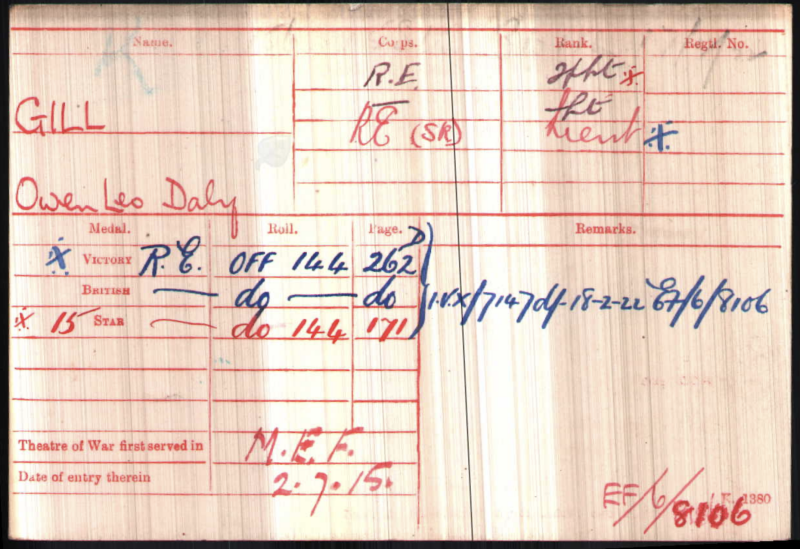

Medal Card for Owen Leo Gill

Poppies in the sand

Helles Memorial, Gallipoli

Owen Leo Gill

Road built by Royal Engineers

[1] Brigadier-General Henry Haggard, commanding 32nd Brigade.

[2] Captain John Francis Mott, 2nd attached 6th Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment, was killed in action on 7th August 1915. Buried in Hill 10 Cemetery, he was the 32 year-old son of the late Col. W. H. Mott, of Bishopton Grange, Ripon, Yorks.; husband of Muriel E. Mott, of 28 Cyril Mansions, Prince of Wales Road, Battersea Park, London.

[2] Sgt. Lionel Frank Nichols, 11th Division Signal Company Royal Engineers, was killed in action on 11th August 1915 (according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission). Commemorated on the Helles Memorial, he was the 23 year-old son of Emily Nichols, of Whyteleafe, Surrey, and the late William Thomas Nichols.

[3] 'Freeman's Journal,' 20th October 1915.

Create Your Own Website With Webador