DR BARRY O'MEARA

In 1822 , a two volume book named Napoleon in Exile was released to critical acclaim. A second edition was released the same year such was it’s popularity. The volumes were adorned with 114 engraved portraits, battle scenes, fold out maps and views. All the work of Nenagh man Dr Barry Edward O’Meara and an account of his time spent with the late Emperor Napoleon.

Barry was the son of Jeremiah O’Meara and Catherine Harpur and was their third child born in 1786. Barry’s father Jeremiah converted to the established church in 1775. This coincided with his acceptance of an awarded of a grant of arms and a Pension of £100 per annum from George III. He had been commended for his actions as a Lieutenant with the 29th Foot (Worcester Regiment) against the Oak-boys uprising at Derry in 1763. Jeremiah married Catherine in 1782 and set about a new career as a Lawyer. It is presumed that Barry was born at their residence at Newtown House in Blackrock although there is also an association with Lissiniskey House outside Nenagh. The grant of arms given to Jeremiah was the same as that given to Thady O’Meara at Lissiniskey which would support a claim that they were of the same bloodline. It is also noteworthy that Newtown in Lissaniskey was part of the greater O’Meara estates. Is the name of the house in Blackrock a direct reference to this?

There is some question as to Barry’s medical training. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, there is no record of him ever having been enrolled at either Trinity College or the Royal College of Surgeons in Stephens Green. In his own words Barry states he was apprenticed to the City Surgeon, Mr Leake and attended his anatomy lectures at the two establishments without any formal enrolment. Nevertheless, having studied Surgery in London, Barry entered the 62nd Regiment of Foot (Wiltshires) in 25/02/1804 as an assistant surgeon. He was 18. He was later given permission by the regiment to attend St Bartholomew’s Hospital to further his post graduate education in 1805.

Barry served in Egypt where the regiment relieved the garrison at Alexandria. From there he was sent to Sicily. Upon arrival in Sicily, Barry was ordered to cross the dangerous Straits of Messina in a rowing boat and scale a two hundred foot cliff face in order to bring medical aid to the sick and wounded in the middle of the second siege at Castello di Scylla. Barry records that he successfully managed to get 49 stretchers down the cliff-face and back to Messina without loss of life. The fortress which originally had been of strategic importance was abandoned to the French but it was effectively now useless as a stronghold. Two sieges and accompanying bombardments had destroyed it’s defences and neutralised its role as a fortress.

In 17/06/1808, despite his here-to-fore heroic exploits, Barry was court-martialled for acting as a second in a duel and cashiered from service as was normal for the time. Other versions state he had been caught pilfering Army goods.

Ultimately, the resilient Barry sailed to Malta where he joined the Navy. He ended up as an assistant surgeon on the H.M.S. Victorious where he spent three years. He was present during the taking of the French ship Rivoli in 1811 as she tried to break out of Venice. Barry was mentioned in despatches by Captain Talbot and promotion was recommended. Following this Barry spent time aboard a number of ships in the West Indies as Senior Surgeon eventually ending up on the Bellerophon as ships surgeon.

On 15/07/1815, Napoleon formerly surrendered to the captain of the Bellerophon, Frederick Lewis Maitland. Napoleon had been on the nearby Isle d’Aix, near La Rochelle hiding out after his abdication as Emperor, from the Prussians and Austrians. An envoy was sent under a flag of truce to discuss Napoleon’s terms for surrender. Terms and conditions were agreed and Napoleon and his loyal retinue joined the Bellerophon at Rochefort. Initially Napoleon had wished to be allowed to travel to America to claim asylum and join his brother Joseph, but this was refused. The Bellerophon was moved under escort to Brixham and later Plymouth while the British government made up their minds as to what next to do. Despite the secrecy surrounding their prisoner, word leaked out and a large amount of day trippers and small vessels surrounded the Bellerophon in the hope of catching a glimpse of the once Emperor and ogre. The government finally made up it’s mind. Despite his wishes to be allowed a small estate in England, Napoleon and his entourage were to be exiled to St Helena in the South Atlantic. Napoleons own physician, Louis-Pierre Maingault refused to accompany his Emperor to St Helena.

This is where Barry seized the opportunity. Napoleon was impressed by the young Irishman’s command of and fluency in both Italian and French and requested he accompany him as a medical attendant. The O’Meara name would not have been unknown to Napoleon as two of that surname were Colonels in his army, Thomas and Guillaume (William), the latter had been gazetted a Baron of the French Empire. Both were descended from the O’Meara’s of Bawn, Nenagh.

The British authorities were pleased that Napoleon should want a British Naval doctor so agreed that Dr O’Meara should accompany Napoleon on the HMS Northumberland to St Helena. Perhaps they thought they might be able to use the Irishman in their dealings with the Emperor and his retinue. No doubt Napoleon would have thought also the Irishman could be manipulated due to the long history of Irish disaffection with the English and the numerous French intrigues and involvements fanning the flames. The 1798 rebellion in Ireland was still within living memory. It took 72 days to voyage to St Helena so Barry and Napoleon were firm friends by landfall.

Upon arrival in St Helena, the opposing lines were drawn with Barry caught in the middle. The French declared the Island was too damp and would cause Napoleon to suffer from Hepatitis or other illness. They demanded he be repatriated lest he die of a tropical disease. The British on the other hand insisted Jamestown, the capital, was perfectly healthy and temperate. This is true, however Longwood has a damp tropical microclimate.

Napoleon and his entourage set up camp in Longwood House Estate and were more or less left to their own devices. Barry found himself visiting Napoleon more and more often and making longer visits. They discussed all topics such as politics, warfare, women or indeed anything that would prove a distraction. At this stage Barry commenced recording in his diary their conversations with Napoleon approval, with the proviso the conversations only be published after Napoleon had died.

Longwood House was a converted Barn and suffered from damp and rats, but Napoleon accepted it though it did not prevent his entourage from being miserable in their new abode. In time it would be rebuilt. The British weren’t allowed on the estate except by invitation. As prisons go it was of the open sort. The island was remote enough for there to be any danger of sudden escape. They were 4000 miles from Capetown, South Africa and 3700 nautical miles from Brazil, South America. Napoleon therefore was allowed the use of horses if he wished to go riding around the island unsupervised. Making the best of a bad lot everything bobbed along nicely with Napoleon querying all British interfering, making irrational demands and generally baiting his gaolers.

There always has to be a antagonist in every tale and in this story it arrived seven months later on 15/04/1816 in the form of Sir Hudson Lowe as Governor General of the island. Previously under the Royal Naval care of Admiral Cockburn, Napoleon had little or no time for the Army Officer class, most of whom had purchased any commissions they had.

Napoleon took an instant dislike to Lowe. He remarked to Barry on 05/05/1816 “he wears the imprint of crime on his face”. Lowe was also an Irishman, from Galway, son of a Scottish surgeon and an Irish mother. Lowe had risen through the ranks having joined up at the age of 12. By all accounts Lowe was a martinet, the type whose own troops would happily fire on. The lax regime Napoleon had enjoyed until now was to end. He was to be confined to the Longwood estate with it’s damp micro-climate and a twelve mile perimeter within which he could hunt. Napoleon was allowed an annual allowance which Lowe actually increased and foods for his table which were not on the British officers list. Restricting Napoleon’s movements to this area backfired for Lowe with Napoleon locking himself away for days in Longwood culminating with Sir Thomas Reade actually banging on the Longwood doors demanding to see General Bonaparte. Napoleon refused to answer to any other name except Napoleon so the reply was sent out, no one of that rank resides here…..and so it went on and on. One of the distractions was the birth at Longwood of a young girl, Napoleone de Montholon on 18/06/1816.

Meanwhile Barry is recording all of these happenings and posting the events in letters to friends in London. In a letter from Barry to Lowe on 28/01/1817, he recounts Napoleon’s plan for the invasion of England and how it would have been achieved. Lowe at this stage tried to interfere and put an end to Barry from seeing Napoleon except only on medical matters. This doesn’t work as Barry is employed by the Royal Navy and not subject to the whims of a government official. One could argue that Lowe was in his rights to try and curtail Barry’s activities and have them confined to medical dealings alone. However we also have to look at Napoleon the great manipulator and the use of Barry as a pawn in his machinations to undermine Lowe. Perhaps a man of a different temperament would have been able to deal with the Corsican corporal. One seems to get the feeling that Lowe is unsure of his position and in awe of his charge. Lowe is not from aristocracy but then neither for that matter was Napoleon. Napoleon however did have the self-confidence and arrogance that Lowe lacked.

Lowe was the type of micro-manager who demanded regular bulletins as to Napoleon’s health. He tried to get Barry removed in favour of an appointee of his own choosing. At one stage Barry offered his resignation to the Admiralty. However this was refused and a letter of admonishment to Lowe told him to put aside any personal differences he may have with Barry and for as long as Napoleon was happy and content with him, Barry was not to be removed from Longwood.

This escalation against Barry only succeeded in drawing Barry deeper and further into the French circle. A letter from Count Bertrand from Longwood dated 13/04/1818, tells Lowe in no uncertain terms that Dr O’Meara is not to be removed and that Napoleon will countenance having no other doctor but Barry. Lowe’s response through an intermediary is to berate Barry for entering into communication with Count Bertrand or informing Napoleon Bonaparte of his resignation without Lowe’s express permission. Eventually all communications between Lowe and both Barry and Longwood ceased. Barry filled his time by translating Napoleon’s memoirs.

It’s worth noting at this stage, the Admiralty were also in receipt of copies of Barry’s letters so were fully aware of not only Lowe’s reports but also the happenings amongst the French at Longwood. Eventually however, a letter from Barry to the Admiralty with the accusation that Lowe had asked him to shorten the Emperor’s life was to end Barry’s stay on the island. The response was basically he had either fabricated the insinuation or if it was true, Barry had grossly violated his duty by concealing the event for some time. On 25/07/1818 Lowe received a letter from the Admiralty demanding Barry’s expulsion from the island. Barry was ordered to leave Longwood the same day and held under arrest until he was shipped off the island in August 1818. Upon arriving in Britain, Barry tried to get Napoleon brought back also for health reasons. He was offered a position as consultant surgeon at Chelsea & Greenwich Naval Hospital on the proviso he remain silent on Napoleon’s health. Two weeks later he was cashiered from the Navy, his pension removed and his name struck from the medical register.

Barry should now have been penniless but Napoleon came to the rescue again in the form of a pension from Napoleon’s mother Letizia and his brother Joseph. Whilst meeting with Madame Mere, Barry suggested she write a letter to the British Parliament demanding her son be taken off St Helena for the sake of his health. Barry completed and published Napoleons memoir on Waterloo. In the daytime he hung Napoleon’s wisdom tooth in his window of his rooms at Edgware Road and offered his services as a dentist.

Napoleon died in St Helena on 05/05/1821. He died of stomach cancer. Barry was now free to publish his diaries. Barry published his Napoleon in Exile in 1822. He had spent the intervening years editing them down to two volumes and therefore was first to get published. The publication was an instant success with police being brought in to control the crowds trying to get copies. It also made Barry a very wealthy man. That and after dinner speaking increased his popularity. There were of course the detractors. The Glasgow Sentinel published a letter from Count Bertrand on 04/12/1822 stating the Count had not been privy to any of the conversations in Barry’s book. That most likely is quite true as no doubt the Count would have been excluded from any medical consultations. This revelation has to be seen in the light of how many other ‘exclusive’ diaries were being published claiming association with Napoleon. Of interest also is an attempt by Lowe to sue Barry for false accusations. This was thrown out by the court who admonished Lowe for taking too long to bring the case to court and was thus subject to the statute of limitations. Lowe would later die in 1844 impoverished and buried without honours.

On 05/02/1823 the 37 year old Barry married by special licence the 67 year old and and twice widowed Theodosia Leigh. With access to her fortune his financial situation was doubly secure. Barry is said to have been married previously but details of this marriage are not known.

It would appear that Barry was genuinely fond of the Emperor. He remained within Napoleon-ist circles long after his return from the island. He also never forgot his Irish roots and was a wholehearted supporter of Daniel O’Connell. Daniel O’Connell remarked that Barry was greatly attached to the memory of Napoleon. O’Connell and O’Meara became good friends. Indeed it was at one of O’Connell’s meetings that Barry caught a chill whilst standing at an open window. Going home he took to his bed and died later of Erysipelas caused by streptococcus. He was buried four days later on 18/06/1836 within St Mary’s Church in Paddington. He was only 54.

In Nenagh and its Neighbourhood, Sheehan records that a nephew/brother of Napoleon II, Prince Jerome stopped at 54 Castle St for refreshments and a relay of horses in July 1857. His ship "La Reine Hortense" was moored on the Shannon at Limerick at the time. The young Prince was touring Ireland incognito. Previously called Devanes It was thereafter known as the Imperial Hotel. We would have known it as Nolans Bar.

In later years, we find an entry in the Irishman dated 14/07/1866 where Napoleon III via a letter to the paper from a priest, is seeking to establish contact with the relatives of Dr Barry O’Meara, such was the esteem the Bonaparte family held for him in his dealings with the Emperor.

Adventurer, author, friend, medic and opportunist, Barry O'Meara is another Nayna man who has made his mark on the world stage

It's Over: Napoleon I at Saint Helena - (Oscar Rex)

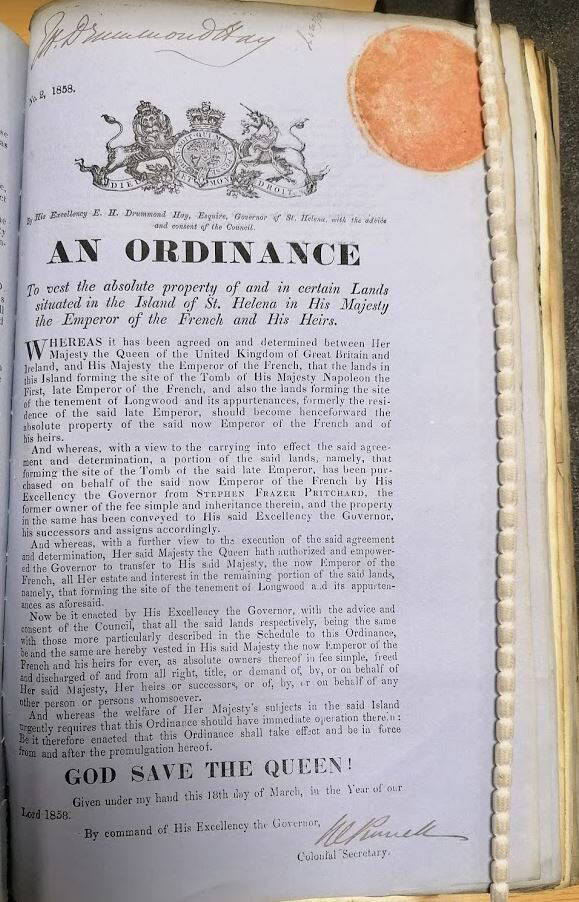

The transfer of the Longwood Estate to the French Government in 1858.

(Following a ticking off by the late Queen Mother after a visit to the island in 1947, the French Government now keeps a permanent French presence to avoid the deterioration of the estate)

Site of the Imperial Hotel at the junction of Peter St and Castle St

Dr Barry Edward O'Meara

Lissiniskey House, Nenagh

HMS Victorious taking the Rivoli

Log entry for HMS Bellerophon on 15/07/1815

Receipt of Napoleon on Bellerophon

Napoleon on Bellerophon by Sir William Orchardson (1880)

The island of St Helena

Longwood estate today after renovation

Longwood House in 1914

Sir Hudson Lowe- Governor of St Helena

Napoleon dictating

Napoleon receiving Lowe

Contemporary cartoon of Lowe and Napoleon

Napoleon with entourage

Napoleon in Exile (published 1822)

Frontispiece with illustration of statue gifted to O'Meara from Napoleon

Napoleons bed on St Helena

Napoleons first grave on St Helena. His body was later removed to Les Invalides in Paris. The grave in St Helena is still maintained by the French Government

Marriage of Barry O'Meara esq. to Dame Theodosia Leigh

Barrys burial in St Mary's Church in Paddington

St Helena stamp commemorating Sir Hudson Lowe and the 150th anniversary of the Abolition of Slavery on the island.

Create Your Own Website With Webador